Святый Боже, Святый крепкий, Святый безсмертный, помилуй насъ

|

|

|

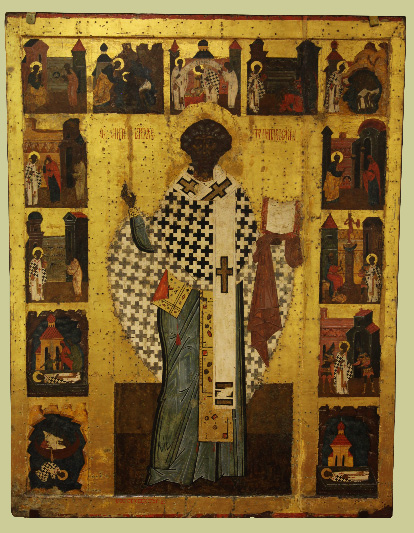

Русское православие честь и почитание Папу.

Russian Orthodoxy honoring and venerating a Pope.

XVI century icon from Архангельская Область – Arkhangelsk Oblast, once in the Никольская Церковь – Church of Saint Nicholas (1763) in Нёнокса – Nyonoksa.

|

|

|

|

Інкерманський Свято-Климентіївський печерний чоловічий монастир, Інкерман, Кримський Півострів

Инкерманский Свято-Климентовский пещерный мужской монастырь, Инкерман, Крымского Полуострова

Inkerman Cave Monastery of Saint Clement, Inkerman, Crimean Peninsula

Greek, Roman, Kievan Rusan, Imperial Russian, Orthodox and Catholic, and hewn and build,

in part with his own hands, by Saint Clement, martyred in Anno Domini 99 or 101 in

Chersonesus - Χερσόνησος (contracted in Medieval Greek as Χερσών - Корсунь - Korsun).

Consecrated by Apostle Saint Peter, the Liber Pontificalis lists Saint Clement as the fourth

pope (r. 92 to 99), the third successor after Peter, after Saints Linus and Anacletus/Cletus.

Saint Cyril – together with his brother Methodius - Κύριλλος καὶ Μεθόδιος / Кѷриллъ и Меѳодїи

- Catholic Patron Saints of Europe and Orthodox Equals to the Apostles - равноапостольные –

brought the relics of Saint Clement to Rome, where they are now with those of Saint Cyril himself

in the Basilica of San Clemente - Basilica di San Clemente.

Except for the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem and the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem,

it is difficult to imagine a place of more symbolic historical significance for the unity of the

Orthodox-Catholic Church which once was and can and should be again, and which is therefore also

a prized target for those forces of evil who would sow dissension in the Church and in Christendom. |

|

|

Свят, Свят, Свят, Господь Саваоф,

Исполнь небо и земля славы Твоея:

Осанна в вышних.

Благословен грядый во имя Господне,

Осанна в вышних. |

| Malie Koreli in Arkhangelsk Oblast. |

|

|

| |

Всѧкое Дыхание Да Хвалит Господ

Every breath praise the Lord |

|

| |

|

|

| |

в Пскове – in Pskov |

|

| |

Свято-Троицкая Сергиева Лавра в Сергиевом Посаде — Holy Trinity Lavra of Saint Sergius in Sergiev Posad |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Церковь в честь Сошествия Святого Духа на Апостолов (Духовская Церковь) — Church in honor of the Descent of the Holy Spirit, built 1476 to 1477 (at left) |

|

| |

Колокольня – Belltower, built, with additions made to the orgininal plan of court architect I. Shchumakher, 1740-70. At 88 meters, the then highest buiding in Russia. |

|

| |

Успенский Собор был заложен по велению Царя Ивана IV Грозного — Cathedral of the Assumption or Cathedral of the Dormition |

|

| |

Built 1559-1585 on orders from Tsar Ivan IV (the Terrible). |

|

| |

This extaordinary architectural ensemble is in the Свято-Троицкая Сергиева Лавра в Сергиевом Посаде — Holy Trinity Lavra of Saint Sergius in Sergiev Posad. |

|

| |

Митрополит Филарет, в миру Василий Михайлович Дроздов (* 26 декабря 1782 [6 января 1783] Коломна, с 22 августа 1826 Митрополит Московский и Коломенский–Москва 19 ноября [1 декабря] 1867 †) |

|

| |

Metropolitan Philaret, secular name Vasily Mikhaylovich Drozdov (* 26 December 1782 [N.S. 6 January 1783] in Kolomna, from 22 August 1826 Metropolitan of Moscow – Moscow 19 November [N.S. 1 December] 1867 †) |

|

|

|

Saint Amvrosy - Ambrose, Monastery of Optina Pustin |

|

What is the Truth? ... painting by N.N. Ghe

|

| |

|

|

| |

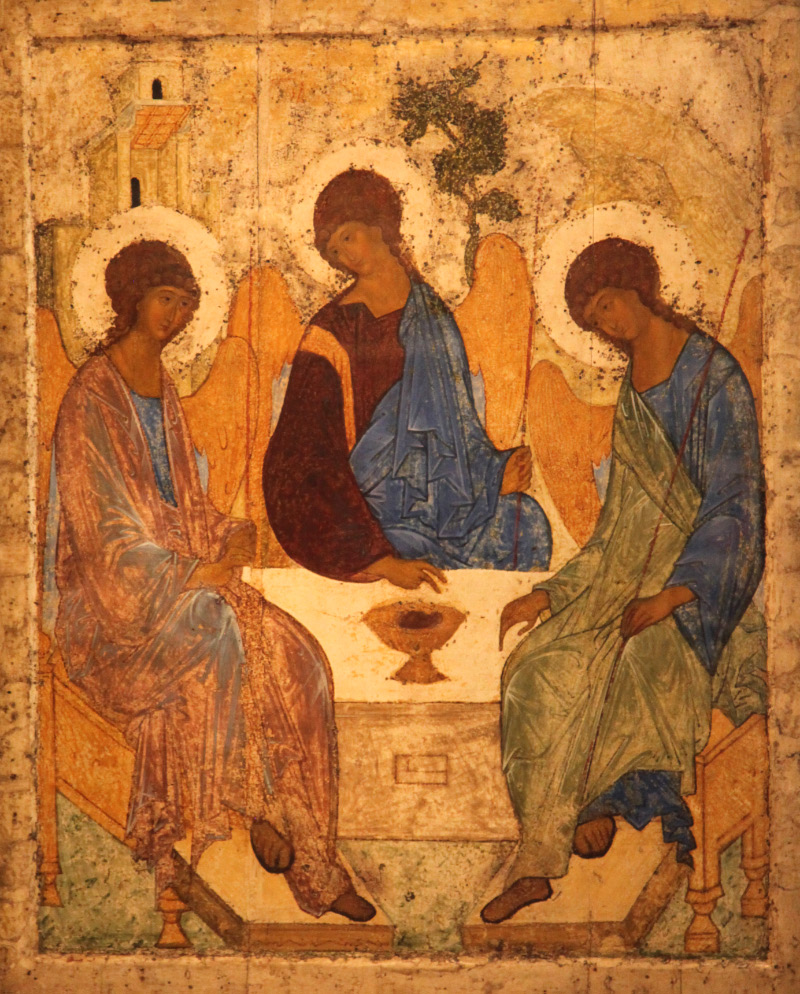

Троица, 1411 год или 1425 - 1427 — Troitsa, icon written in 1411 or 1425 - 1427

Андрей Рублёв - Saint Andrei Rublyov (* c. 1360 - 29 I 1430 †)

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Ἐλεούσα – Eleousa – tenderness – showing mercy – Элеуса – Елеуса – Умиление – Madonna Eleusa – Virgin of Tenderness |

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

Воскрешение дочери Иаира (1871), И.Е. Репин - Jesus raising the daughter of Jairus by Ilya Repin, Russian Museum, Saint Petersburg |

| |

|

|

| Let him among you who is without sin be the first to throw a stone at her ... – John 8:7 –. ... Forgiveness - Прощение . |

| |

| Judge not, that you be not judged. For with the judgment you pronounce you will be judged, and the measure you give will be the measure you get. Why do you see the speck that is in your brother’s eye, but do not notice the log that is in your own eye? Or how can you say to your brother, ‘Let me take the speck out of your eye,’ when there is the log in your own eye? You hypocrite, first take the log out of your own eye, and then you will see clearly to take the speck out of your brother’s eye. – Matthew 7:1-5 – |

| |

| |

| But take heed, brothers and sisters. Elsewhere in the Bible, we are not only permitted, we are required to exercise discernment, and to act upon such discernment: |

| But immorality and all impurity or covetousness must not even be named among you, as is fitting among saints. Let there be no filthiness, nor silly talk, nor levity, which are not fitting; but instead let there be thanksgiving. Be sure of this, that no immoral or impure man, or one who is covetous (that is, an idolater), has any inheritance in the kingdom of Christ and of God. Let no one deceive you with empty words, for it is because of these things that the wrath of God comes upon the sons of disobedience. Therefore do not associate with them, for once you were darkness, but now you are light in the Lord; walk as children of light (for the fruit of light is found in all that is good and right and true), and try to learn what is pleasing to the Lord. Take no part in the unfruitful works of darkness, but instead expose them. – Ephesians 5:3-11 [emphasis added]– |

| |

Russia and the Russian Orthodox Church do stand in a special position as regards the dialogues among the Oriental Orthodox, the Orthodox and the Catholics and as regards the process of Christian and ecclesiological re-unification, and this not only because in Realpolitik they are actually and potentially a whole lot more numerous than the Greeks. So too within European Christendom, the Russians are special, and they have a special and in important senses leadership role to play.

To many Descendants of European Christendom other than Russians the forgoing may seems strange. Indeed to play a holy role the Russians will need to rethink and change much within themselves, not least the mass fashion in recent decades to try to view the atheist Communist period as somehow a continuation of and in continuity with — rather than an abominable interruption from — Russia's holy role within European Christendom and Christendom universal. Embracing evil in order to manufacture martyrs is not worthy of the least among Christian societies. Lapsed- or atheist- Jews may have started ... well, clearly did start and lead Bolshevism. Equally clear is that they could not have and did not do it alone. As difficult as it may be to acknowledge this about one's grandfathers and fathers, how can there be reconciliation, much less leadership, without truth? |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Εικονοστάσιο – Иконостас – Iconostasis with icons (to the viewer's left) of:

Άγιος Βασίλειος ὁ Μέγας – Святой Василий Великий – Saint Basil of Caesarea, Basil the Great (* c. 330 Caesarea, Cappadocia to 1 or 2 January 379 †)

and (to the viewer's right),

Άγιος Ιωάννης ο Χρυσόστομος – Святой Иоанн Златоуст – Saint John Chrysostom (* c. 349 Antioch – Comana in Pontus 14 September 407 †),

both Doctors of the Church and, along with

Άγιος Γρηγόριος ὁ Ναζιανζηνός – Святой Григорий Богослов – Saint Gregory of Nazianzus, Gregory the Theologian (* c. 329 – 25 January 390 †),

| Οἱ Τρεῖς Ἱεράρχαι – Собор вселенских трёх Учителей и Святителей – the Three Great Hierarchs of the Universal Church. |

And other triplet is formed — The Cappadocian Fathers, or the Three Cappadocians — when, to Gregory of Nazianzus and Basil, Basil's younger brother is added:

Άγιος Γρηγόριος Νύσσης – Святой Григорий Нисский – Saint Gregory of Nyssa (* c. 335 – c. 395 †).

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

Appearance of Christ to the People, painting by A.A. Ivanov - А. А. Иванов (1806 - 1858) |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

SS. Ambrosius – Nicolaus – Maurus – Placidus – Matrona |

|

|

| |

One of the most extraordinary collections of relics in Russia or in the world, including for the circumstance that the relics of the two smaller reliquaries were gifts from the Patriarchate of Rome — the Catholic Church — to the Patriarchate of Moscow and All Rus. To the viewer's left, the reliquary contains relics (body parts) of Sanctus Aurelius Ambrosius, Doctor Ecclesiae – Doctor of the Church Saint Ambrose – Амвросий Медиоланский (* 339 in Trier; 4 April 397 in Milan†) The middle reliquary contains body-part relics of three saints, including Николай Чудотворец – Άγιος Νικόλαος Μυριώτης – Sanctus Nicolaus – Saint Nicholas the Wonderworker, certainly one of the most widely venerated of saints in Russia (* c. 270 in Patara, Asia Minor – 6 December c. 345 in Myra, Asia Minor † ); Saint Maurus – Мавр and Saint Placidus– Плацида (6th century †), both Benedictine monks and abbots and both students of Sanctus Benedictus de Nursia – Святой Бенедикт Нурсийский – Benedict of Nursia , Patron Saint of Europe. The larger reliquary to the viewer's right contains relics of Блаженная Матрона Московская – Saint Matrona the Wonderworker of Moscow (* 1881 - 2 May 1952 in Moscow †), though very far away from these other saints in time and place, she is united with them in suffering and sanctity. Presently these are housed in a small wooden chapel, a Часовня, next to the Cathedral of the Archangel Michael in Архангельск – Arkhangelsk, which in July of 2015 is under construction. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| мощи святого Иоанна Тульского - Saint John of Tula |

|

... Успенский Кафедральный Собор, Тула - Dormition Cathedral, Tula |

|

|

|

|

The Catholic Crusader Connection

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A throne for Russian Emperor Павел I – Pavel (r. 1796 - 1801) in Versailles, probably stolen during the treacherous invasion of Napoleon's forces in June of 1798. After the Freemasonic French Revolution, of all temporal sovereigns in European Christendom Emperor Pavel (Paul) of Russia gave refuge to the greatest number of Knights Hospitaller now effectively exiled from Malta, crowning a tradition of cooperation extending back at least to the time of Peter the Great and the embassy of Field Marshal Boris Sheremetev to Malta in 1698. In 1799 the Orthodox Emperor Pavel (r. 6 (17 N.S.) November 1796 – 12 (24 N.S.) March 1801 assassination †) was made the Grand Master of the Catholic Knights Hospitaller and the Maltese Order was introduced into the heraldry of the Russian Empire.

|

|

|

|

Михаил Десницкий, Митрополит Санкт-Петербургский и Ладожский 26 марта 1818 – 24 марта 1821 и член Святейшего Правительствующего Синода – Mikhail Desnitsky, Metropolitan of Saint Petersburg and Ladoga, March 26, 1818 - March 24, 1821, and a member of the Holy Synod. Portrait by Borovikovsky in the Михайловский Замок – Saint Michael's Castle of Saint Petersburg of the Russian Orthodox Metropolitan Mikhail wearing the Maltese Order:

Госпитальеры Иерусалимский, Родосский и Мальтийский Суверенный Военный Странноприимный Орден Святого Иоанна – Ordre souverain militaire hospitalier de Saint-Jean, de Jérusalem, de Rhodes et de Malte – The Sovereign Military Hospitaller Order of Saint John of Jerusalem of Rhodes and of Malta, Christian, medical and military from 1099 Anno Domini to the present. |

|

|

|

| |

The only 'god-bearing' people on earth |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Знаете ли вы, — начал он почти грозно, принагнувшись вперед на стуле, сверкая взглядом и подняв перст правой руки вверх пред собою (очевидно не примечая этого сам), — знаете ли вы, кто теперь на всей земле единственный народ "богоносец", грядущий обновить и спасти мир именем нового бога и кому единому даны ключи жизни и нового слова... Знаете ли вы, кто этот народ и как ему имя? |

|

“Do you know,” he began, with flashing eyes, almost menacingly, bending right forward in his chair, raising the forefinger of his right hand above him (obviously unaware that he was doing so), “do you know who are the only 'god-bearing' people on earth, destined to regenerate and save the world in the name of a new God, and to whom are given the keys of life and of the new world . . . Do you know which is that people and what is its name?” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— По вашему приему я необходимо должен заключить, и, кажется, как можно скорее, что это народ русский... |

|

“From your manner I am forced to conclude, and I think I may as well do so at once, that it is the Russian people.” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— И вы уже смеетесь, о, племя! — рванулся было Шатов. |

|

“And you can laugh, oh, what a race!” Shatov burst out. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Успокойтесь, прошу вас; напротив, я именно ждал чего-нибудь в этом роде. |

|

“Calm yourself, I beg of you; on the contrary, I was expecting something of the sort from you.” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Ждали в этом роде? А самому вам не знакомы эти слова? |

|

“You expected something of the sort? And don't you know those words yourself?” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Очень знакомы; я слишком предвижу, к чему вы клоните. Вся ваша фраза и даже выражение народ "богоносец" есть только заключение нашего с вами разговора, происходившего слишком два года назад, за границей, незадолго пред вашим отъездом в Америку... По крайней мере сколько я могу теперь припомнить. |

|

“I know them very well. I see only too well what you're driving at. All your phrases, even the expression 'god-bearing people' is only a sequel to our talk two years ago, abroad, not long before you went to America. . . . At least, as far as I can recall it now.” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Это ваша фраза целиком, а не моя. Ваша собственная, а не одно только заключение нашего разговора. "Нашего" разговора совсем и не было: был учитель, вещавший огромные слова, и был ученик, воскресший из мертвых. Я тот ученик, а вы учитель. |

|

“It's your phrase altogether, not mine. Your own, not simply the sequel of our conversation. 'Our' conversation it was not at all. It was a teacher uttering weighty words, and a pupil who was raised from the dead. I was that pupil and you were the teacher.” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Но если припомнить, вы именно после слов моих как раз и вошли в то общество и только потом уехали в Америку. |

|

“But, if you remember, it was just after my words you joined their society, and only afterwards went away to America.” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Да, и я вам писал о том из Америки; я вам обо всем писал. Да, я не мог тотчас же оторваться с кровью от того, к чему прирос с детства, на что пошли все восторги моих надежд и все слезы моей ненависти... Трудно менять богов. Я не поверил вам тогда, потому что не хотел верить, и уцепился в последний раз за этот помойный клоак... Но семя осталось и возросло. Серьезно, скажите серьезно, не дочитали письма моего из Америки? Может быть не читали вовсе? |

|

“Yes, and I wrote to you from America about that. I wrote to you about everything. Yes, I could not at once tear my bleeding heart from what I had grown into from childhood, on which had been lavished all the raptures of my hopes and all the tears of my hatred. . . . It is difficult to change gods. I did not believe you then, because I did not want to believe, I plunged for the last time into that sewer. . . . But the seed remained and grew up. Seriously, tell me seriously, didn't you read all my letter from America, perhaps you didn't read it at all?” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Я прочел из него три страницы, две первые и последнюю, и кроме того бегло переглядел средину. Впрочем я все собирался... |

|

“I read three pages of it. The two first and the last. And I glanced through the middle as well. But I was always meaning . . .” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Э, всё равно, бросьте, к чорту! — махнул рукой Шатов. — Если вы отступились теперь от тогдашних слов про народ,. то как могли вы их тогда выговорить?.. Вот что давит меня теперь. |

|

“Ah, never mind, drop it! Damn it!” cried Shatov, waving his hand. .”If you've renounced those words about the people now, how could you have uttered them then? . . . That's what crushes me now.” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Не шутил же я с вами и тогда; убеждая вас, я, может, еще больше хлопотал о себе, чем о вас, — загадочно произнес Ставрогин. |

|

“I wasn't joking with you then; in persuading you I was perhaps more concerned with myself than with you,” Stavrogin pronounced enigmatically. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Не шутили! В Америке я лежал три месяца на соломе, рядом с одним... несчастным и узнал от него, что в то же самое время, когда вы насаждали в моем сердце бога и родину, в то же самое время даже может быть в те же самые дни, вы отравили сердце этого несчастного, этого маньяка, Кириллова, ядом... Вы утверждали в нем ложь и клевету и довели разум его до исступления... Подите, взгляните на него теперь, это ваше создание... Впрочем вы видели. |

|

“You weren't joking! In America I was lying for three months on straw beside a hapless creature, and I learnt from him that at the very time when you were sowing the seed of God and the Fatherland in my heart, at that very time, perhaps during those very days, you were infecting the heart of that hapless creature, that maniac Kirillov, with poison . . . you confirmed false malignant ideas in him, and brought him to the verge of insanity. . . . Go, look at him now, he is your creation . . . you've seen him though.” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Во-первых, замечу вам, что сам Кириллов сейчас только сказал мне, что он счастлив и что он прекрасен. Ваше предположение о том, что всё это произошло в одно и то же время, почти верно; ну, и что же из всего этого? Повторяю, я вас ни того, ни другого не обманывал. |

|

“In the first place, I must observe that Kirillov himself told me that he is happy and that he's good. Your supposition that all this was going on at the same time is almost correct. But what of it? I repeat, I was not deceiving either of you.” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Вы атеист? Теперь атеист? |

|

“Are you an atheist? An atheist now?” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Да. |

|

“Yes.” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— А тогда? |

|

“And then?” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Точно так же, как и тогда. |

|

“Just as I was then.” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Я не к себе просил у вас уважения, начиная разговор; с вашим умом, вы бы могли понять это, — в негодовании пробормотал Шатов. |

|

“I wasn't asking you to treat me with respect when I began the conversation. With your intellect you might have understood that,” Shatov muttered indignantly. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Я не встал с первого вашего слова, не закрыл разговора, не ушел от вас, а сижу до сих пор и смирно отвечаю на ваши вопросы и... крики, стало быть, не нарушил еще к вам уважения. |

|

“I didn't get up at your first word, I didn't close the conversation, I didn't go away from you, but have been sitting here ever since submissively answering your questions and . . . cries, so it seems I have not been lacking in respect to you yet.” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Шатов прервал, махнув рукой: |

|

Shatov interrupted, waving his hand. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Вы помните выражение ваше: "атеист не может быть русским", "атеист тотчас же перестает быть русским", помните это? |

|

“Do you remember your expression that 'an atheist can't be a Russian,' that 'an atheist at once ceases to be a Russian'? Do you remember saying that?” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Да? — как бы переспросил Николай Всеволодович. |

|

“Did I?” Nikolay Vsyevolodovitch questioned him back. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

— Вы спрашиваете? Вы забыли? А между тем это одно из самых точнейших указаний на одну из главнейших особенностей русского духа, вами угаданную. Не могли вы этого забыть? Я напомню вам больше, — высказали тогда же: "не православный не может быть русским". |

|

“You ask? You've forgotten? And yet that was one of the truest statements of the leading peculiarity of the Russian soul, which you divined. You can't have forgotten it! I will remind you of something else: you said then that 'a man who was not orthodox could not be Russian.'” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Я полагаю, что это славянофильская мысль. |

|

“I imagine that's a Slavophile idea.” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Нет; нынешние славянофилы от нее откажутся. Нынче народ поумнел. Но вы еще дальше шли: вы веровали, что римский католицизм уже не есть христианство; вы утверждали, что Рим провозгласил Христа, поддавшегося на третье дьяволово искушение, и что, возвестив всему свету, что Христос без царства земного на земле устоять не может, католичество тем самым провозгласило антихриста и тем погубило весь западный мир. Вы именно указывали, что если мучается Франция, то единственно по вине католичества, ибо отвергла смрадного бога римского, а нового не сыскала. Вот что вы тогда могли говорить! Я помню наши разговоры. |

|

“The Slavophils of to-day disown it. Nowadays, people have grown cleverer. But you went further: you believed that Roman Catholicism was not Christianity; you asserted that Rome proclaimed Christ subject to the third temptation of the devil. Announcing to all the world that Christ without an earthly kingdom cannot hold his ground upon earth, Catholicism by so doing proclaimed Antichrist and ruined the whole Western world. You pointed out that if France is in agonies now it's simply the fault of Catholicism, for she has rejected the iniquitous God of Rome and has not found a new one. That's what you could say then! I remember our conversations.” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Если б я веровал, то, без сомнения, повторил бы это и теперь; я не лгал, говоря как верующий, — очень серьезно произнес Николай Всеволодович. — Но уверяю вас, что на меня производит слишком неприятное впечатление это повторение прошлых мыслей моих. Не можете ли вы перестать? |

|

“If I believed, no doubt I should repeat it even now. I wasn't lying when I spoke as though I had faith,” Nikolay Vsyevolodovitch pronounced very earnestly. “But I must tell you, this repetition of my ideas in the past makes a very disagreeable impression on me. Can't you leave off?” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Если бы веровали? — вскричал Шатов, не обратив ни малейшего внимания на просьбу. — Но не вы ли говорили мне, что если бы математически доказали вам, что истина вне Христа, то вы бы согласились лучше остаться со Христом, нежели с истиной? Говорили вы это? Говорили? |

|

“If you believe it?” repeated Shatov, paying not the slightest attention to this request. “But didn't you tell me that if it were mathematically proved to you that the truth excludes Christ, you'd prefer to stick to Christ rather than to the truth? Did you say that? Did you? '' |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Но позвольте же и мне наконец спросить, — возвысил голос Ставрогин, — к чему ведет весь этот нетерпеливый и... злобный экзамен? |

|

“But allow me too at last to ask a question,” said Nikolay Vsyevolodovitch, raising his voice. “What is the object of this irritable and . . . malicious cross-examination?” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Этот экзамен пройдет навеки и никогда больше не напомнится вам. |

|

“This examination will be over for all eternity, and you will never hear it mentioned again.” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Вы всё настаиваете, что мы вне пространства и времени... |

|

“You keep insisting that we are outside the limits of time and space.” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Молчите! — вдруг крикнул Шатов, — я глуп и неловок, но погибай мое имя в смешном! Дозволите ли вы мне повторить пред вами всю главную вашу тогдашнюю мысль... О, только десять строк, одно заключение. |

|

“Hold your tongue!” Shatov cried suddenly. “I am stupid and awkward, but let my name perish in ignominy! Let me repeat your leading idea. . . . Oh, only a dozen lines, only the conclusion.” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Повторите, если только одно заключение... Ставрогин сделал было движение взглянуть на часы, но удержался и не взглянул. Шатов принагнулся опять на стуле и, на мгновение, даже опять было поднял палец. |

|

“Repeat it, if it's only the conclusion . . . .” Stavrogin made a movement to look at his watch, but restrained himself and did not look. Shatov bent forward in his chair again and again held up his finger for a moment. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Ни один народ, — начал он, как бы читая по строкам и в то же время продолжая грозно смотреть на Ставрогина, — ни один народ еще не устраивался на началах науки и разума; не было ни разу такого примера, разве на одну минуту, по глупости. Социализм по существу своему уже должен быть атеизмом, ибо именно провозгласил, с самой первой строки, что он установление атеистическое и намерен устроиться на началах науки и разума исключительно. Разум и наука в жизни народов всегда, теперь и с начала веков, исполняли лишь должность второстепенную и служебную; так и будут исполнять до конца веков. Народы слагаются и движутся силой иною, повелевающею и господствующею, но происхождение которой неизвестно и необъяснимо. Эта сила есть сила неутолимого желания дойти до конца и в то же время конец отрицающая. Это есть сила беспрерывного и неустанного подтверждения своего бытия и отрицания смерти. Дух жизни, как говорит писание, "реки воды живой", иссякновением которых так угрожает Апокалипсис. Начало эстетическое, как говорят философы, начало нравственное, как отожествляют они же. "Искание бога", как называю я всего проще. Цель всего движения народного, во всяком народе и во всякий период его бытия, есть единственно лишь искание бога, бога своего, непременно собственного, и вера в него как в единого истинного. Бог есть синтетическая личность всего народа, взятого с начала его и до конца. Никогда еще не было, чтоб у всех или у многих народов был один общий бог, но всегда и у каждого был особый. Признак уничтожения народностей, когда боги начинают становиться общими. Когда боги становятся общими, то умирают боги и вера в них вместе с самими народами. Чем сильнее народ, тем особливее его бог. Никогда еще не было народа без религии, то-есть без понятия о зле и добре. У всякого народа свое собственное понятие о зле и добре и свое собственное зло и добро. Когда начинают у многих народов становиться общими понятия о зле и добре, тогда вымирают народы, и тогда самое различие между злом и добром начинает стираться и исчезать. Никогда разум не в силах был определить зло и добро, или даже отделить зло от добра, хотя приблизительно; напротив, всегда позорно и жалко смешивал; наука же давала разрешения кулачные. В особенности этим отличалась полунаука, самый страшный бич человечества, хуже мора, голода и войны, не известный до нынешнего столетия. Полунаука — это деспот, каких еще не приходило до сих пор никогда. Деспот, имеющий своих жрецов и рабов, деспот, пред которым всё преклонилось с любовью и суеверием, до сих пор немыслимым, пред которым трепещет даже сама наука и постыдно потакает ему. Всё это ваши собственные слова, Ставрогин, кроме только слов о полунауке; эти мои, потому что я сам только полунаука, а стало быть, особенно ненавижу ее. В ваших же мыслях и даже в самых словах я не изменил ничего, ни единого слова. |

|

“Not a single nation,” he went on, as though reading it line by line, still gazing menacingly at Stavrogin, “not a single nation has ever been founded on principles of science or reason. There has never been an example of it, except for a brief moment, through folly. Socialism is from its very nature bound to be atheism, seeing that it has from the very first proclaimed that it is an atheistic organisation of society, and that it intends to establish itself exclusively on the elements of science and reason. Science and reason have, from the beginning of time, played a secondary and subordinate part in the life of nations; so it will be till the end of time. Nations are built up and moved by another force which sways and dominates them, the origin of which is unknown and inexplicable: that force is the force of an insatiable desire to go on to the end, though at the same time it denies that end. It is the force of the persistent assertion of one's own existence, and a denial of death. It's the spirit of life, as the Scriptures call it, 'the river of living water,' the drying up of which is threatened in the Apocalypse. It's the aesthetic principle, as the philosophers call it, the ethical principle with which they identify it, 'the seeking for God,' as I call it more simply. The object of every national movement, in every people and at every period of its existence is only the seeking for its god, who must be its own god, and the faith in Him as the only true one. God is the synthetic personality of the whole people, taken from its beginning to its end. It has never happened that all, or even many, peoples have had one common, god, but each has always had its own. It's a sign of the decay of nations when they begin to have gods in common. When gods begin to be common to several nations the gods are dying and the faith in them, together with the nations themselves. The stronger a people the more individual their God. There never has been a nation without a religion, that is, without an idea of good and evil. Every people has its own conception of good and evil, and its own good and evil. When the same conceptions of good and evil become prevalent in several nations, then these nations are dying, and then the very distinction between good and evil is beginning to disappear. Reason has never had the power to define good and evil, or even to distinguish between good and evil, even approximately; on the contrary, it has always mixed them up in a disgraceful and pitiful way; science has even given the solution by the fist. This is particularly characteristic of the half-truths of science, the most terrible scourge of humanity, unknown till this century, and worse than plague, famine, or war. A half-truth is a despot .. such as has never been in the world before. A despot that has its priests and its slaves, a despot to whom all do homage with love and superstition hitherto inconceivable, before which science itself trembles and cringes in a shameful way. These are your own words, Stavrogin, all except that about the half-truth; that's my own because I am myself a case of half-knowledge, and that's why I hate it particularly. I haven't altered anything of your ideas or even of your words, not a syllable.” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Не думаю, чтобы не изменили, — осторожно заметил Ставрогин; — вы пламенно приняли и пламенно переиначили, не замечая того. Уж одно то, что вы бога низводите до простого аттрибута народности... |

|

“I don't agree that you've not altered anything,” Stavrogin observed cautiously. “You accepted them with ardour, and in your ardour have transformed them unconsciously. The very fact that you reduce God to a simple attribute of nationality . . . ” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Он с усиленным и особливым вниманием начал вдруг следить за Шатовым, и не столько за словами его, сколько за ним самим. |

|

He suddenly began watching Shatov with intense and peculiar attention, not so much his words as himself. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Низвожу бога до аттрибута народности? — вскричал Шатов, — напротив, народ возношу до бога. Да и было ли когда-нибудь иначе? Народ — это тело божие. Всякий народ до тех только пор и народ, пока имеет своего бога особого, а всех остальных на свете богов исключает безо всякого примирения; пока верует в то, что своим богом победит и изгонит из мира всех остальных богов. Так веровали все с начала веков, все великие народы по крайней мере, все сколько-нибудь отмеченные, все стоявшие во главе человечества. Против факта идти нельзя. Евреи жили лишь для того, чтобы дождаться бога истинного, и оставили миру бога истинного. Греки боготворили природу и завещали миру свою религию, то-есть философию и искусство. Рим обоготворил народ в государстве и завещал народам государство. Франция в продолжение всей своей длинной истории была одним лишь воплощением и развитием идеи римского бога, и если сбросила наконец в бездну своего римского бога и ударилась в атеизм, который называется у них покамест социализмом, то единственно потому лишь, что атеизм всё-таки здоровее римского католичества. Если великий народ не верует, что в нем одном истина (именно в одном и именно исключительно), если не верует, что он один способен и призван всех воскресить и спасти своею истиной, то он тотчас же перестает быть великим народом и тотчас же обращается в этнографический материал, а не в великий народ. Истинный великий народ никогда не может примириться со второстепенною ролью в человечестве, или даже с первостепенною, а непременно и исключительно с первою. Кто теряет эту веру, тот уже не народ. Но истина одна, а, стало быть, только единый из народов и может иметь бога истинного, хотя бы остальные народы и имели своих особых и великих богов. Единый народ "богоносец" — это- русский народ и... и... и неужели, неужели вы меня почитаете за такого дурака, Ставрогин, — неистово возопил он вдруг, — который уж и различить не умеет, что слова его в эту минуту или старая, дряхлая дребедень, перемолотая на всех московских славянофильских мельницах, или совершенно новое слово, последнее слово, единственное слово обновления и воскресения и... и какое мне дело до вашего смеха в эту минуту! Какое мне дело до того, что вы не понимаете меня совершенно, совершенно, ни слова, ни звука!.. О, как я презираю ваш гордый смех и взгляд в эту минуту! |

|

“I reduce God to the attribute of nationality?” cried Shatov. “On the contrary, I raise the people to God. And has it ever been otherwise? The people is the body of God. Every people is only a people so long as it has its own god and excludes all other gods on earth irreconcilably; so long as it believes that by its god it will conquer and drive out of the world all other gods. Such, from the beginning of time, has been the belief of all great nations, all, anyway, who have been specially remarkable, all who have been leaders of humanity. There is no going against facts. The Jews lived only to await the coming of the true God and left the world the true God. The Greeks deified nature and bequeathed the world their religion, that is, philosophy and art. Rome deified the people in the State, and bequeathed the idea of the State to the nations. France throughout her long history was only the incarnation and development of the Roman god, and if they have at last flung their Roman god into the abyss and plunged into atheism, which, for the time being, they call socialism, it is solely because socialism is, anyway, healthier than Roman Catholicism. If a great people does not believe that the truth is only to be found in itself alone (in itself alone and in it exclusively); if it does not believe that it alone is fit and destined to raise up and save all the rest by its truth, it would at once sink into being ethnographical material, and not a great people. A really great people can never accept a secondary part in the history of Humanity, nor even one of the first, but will have the first part. A nation which loses this belief ceases to be a nation. But there is only one truth, and therefore only a single one out of the nations can have the true God, even though other nations may have great gods of their own. Only one nation is 'god-bearing,' that's the Russian people, and . . . and . . . and can you think me such a fool, Stavrogin,” he yelled frantically all at once, “that I can't distinguish whether my words at this moment are the rotten old commonplaces that have been ground out in all the Slavophile mills in Moscow, or a perfectly new saying, the last word, the sole word of renewal and resurrection, and . . . and what do I care for your laughter at this minute! What do I care that you utterly, utterly fail to understand me, not a word, not a sound! Oh, how I despise your haughty laughter and your look at this minute!” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Он вскочил с места; даже пена показалась на губах его. |

|

He jumped up from his seat; there was positively foam on his lips. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Напротив, Шатов, напротив, — необыкновенно серьезно и сдержанно проговорил Ставрогин, не подымаясь с места, — напротив, вы горячими словами вашими воскресили во мне много чрезвычайно сильных воспоминаний. В ваших словах я признаю мое собственное настроение два года назад, и теперь уже я не скажу вам, как давеча, что вы мои тогдашние мысли преувеличили. Мне кажется даже, что они были еще исключительнее, еще самовластнее, и уверяю вас в третий раз, что я очень желал бы подтвердить всё, что вы теперь говорили, даже до последнего слова, но... |

|

“On the contrary Shatov, on the contrary,” Stavrogin began with extraordinary earnestness and self-control, still keeping his seat, “on the contrary, your fervent words have revived many extremely powerful recollections in me. In your words I recognise my own mood two years ago, and now I will not tell you, as I did just now, that you have exaggerated my ideas. I believe, indeed, that they were even more exceptional, even more independent, and I assure you for the third time that I should be very glad to confirm all that you've said just now, every syllable of it, but . . . ” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Но вам надо зайца? |

|

“But you want a hare!” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Что-о? |

|

“Wh-a-t?” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Ваше же подлое выражение, — злобно засмеялся Шатов, усаживаясь опять: — "чтобы сделать соус из зайца, надо зайца, чтобы уверовать в бога, надо бога", это вы в Петербурге, говорят, приговаривали, как Ноздрев, который хотел поймать зайца за задние ноги. |

|

“Your own nasty expression,” Shatov laughed spitefully, sitting down again. “To cook your hare you must first catch it, to believe in God you must first have a god. You used to say that in Petersburg, I'm told, like Nozdryov, who tried to catch a hare by his hind legs.” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Нет, тот именно хвалился, что уж поймал его. Кстати, позвольте однако же и вас обеспокоить вопросом, тем более, что я, мне кажется, имею на него теперь полное право. Скажите мне: ваш-то заяц пойман ли, аль еще бегает? |

|

“No, what he did was to boast he'd caught him. By the way, allow me to trouble you with a question though, for indeed I think I have the right to one now. Tell me, have you caught your hare?” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Не смейте меня спрашивать такими словами, спрашивайте другими, другими! — весь вдруг задрожал Шатов. |

|

“Don't dare to ask me in such words! Ask differently, quite differently.” Shatov suddenly began trembling all over. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Извольте, другими, — сурово посмотрел на него Николай Всеволодович; — я хотел лишь узнать: веруете вы сами в бога или нет? |

|

“Certainly I'll ask differently.” Nikolay Vsyevolodovitch looked coldly at him. “I only wanted to know, do you believe in God, yourself?” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Я верую в Россию, я верую в ее православие... Я верую в тело Христово... Я верую, что новое пришествие совершится в России... Я верую... — залепетал в исступлении Шатов. |

|

“I believe in Russia. . . . I believe in her orthodoxy. . . . I believe in the body of Christ. . . . I believe that the new advent will take place in Russia. . . . I believe . . . ” Shatov muttered frantically. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— А в бога? В бога? |

|

“And in God? In God?” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Я... я буду веровать в бога. |

|

“I . . . I will believe in God.” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Ни один мускул не двинулся в лице Ставрогина. Шатов пламенно, с вызовом, смотрел на него, точно сжечь хотел его своим взглядом. |

|

Not one muscle moved in Stavrogin's face. Shatov looked passionately and defiantly at him, as though he would have scorched him with his eyes. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Я ведь не сказал же вам, что я не верую вовсе! — вскричал он наконец; — я только лишь знать даю, что я несчастная, скучная книга и более ничего покамест, покамест... Но погибай мое имя! Дело в вас, а не во мне... Я человек без таланта и могу только отдать свою кровь и ничего больше, как всякий человек без таланта. Погибай же и моя кровь! Я об вас говорю, я вас два года здесь ожидал... Я для вас теперь полчаса пляшу нагишом. Вы, вы одни могли бы поднять это знамя!.. |

|

“I haven't told you that I don't believe,”, he cried at last. “I will only have you know that I am a luckless, tedious book, and nothing more so far, so far. . . . But confound me! We're discussing you not me. . . . I'm a man of no talent, and can only give my blood, nothing more, like every man without talent; never mind my blood either! I'm talking about you. I've been waiting here two years for you. . . . Here I've been dancing about in my nakedness before you for the last half-hour. You, only you can raise that flag! . . .” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Он не договорил и как бы в отчаянии, облокотившись на стол, подпер обеими руками голову. |

|

He broke off, and sat as though in despair, with his elbows on the table and his head in his hands. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Я вам только кстати замечу, как странность, — перебил вдруг Ставрогин, — почему это мне все навязывают какое-то знамя? Петр Верховенский тоже убежден, что я мог бы "поднять у них знамя", по крайней мере мне передавали его слова. Он задался мыслию, что я мог бы сыграть для них роль Стеньки Разина "по необыкновенной способности к преступлению", — тоже его слова.

|

|

“I merely mention it as something queer,” Stavrogin interrupted suddenly. “Every one for some inexplicable reason keeps foisting a flag upon me. Pyotr Verhovensky, too, is convinced that I might' raise his flag,' that's how his words were repeated to me, anyway. He has taken it into his head that I'm capable of playing the part of Stenka Razin for them, 'from my extraordinary aptitude for crime,' his saying too.” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Как? — спросил Шатов, — "по необыкновенной способности к преступлению"? |

|

“What?” cried Shatov, “'from your extraordinary aptitude for crime'?” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Именно. |

|

“Just so.” |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

— Гм. А правда ли, что вы — злобно ухмыльнулся он, — правда ли, что вы принадлежали в Петербурге к скотскому сладострастному секретному обществу? Правда ли, что маркиз де-Сад мог бы у вас поучиться? Правда ли, что вы заманивали и развращали детей? Говорите, не смейте лгать, — вскричал он, совсем выходя из себя, — Николай Ставрогин не может лгать пред Шатовым, бившим его по лицу! Говорите всё, и если правда, я вас тотчас же, сейчас же убью, тут же на месте! |

|

“H'm! And is it true?” he asked, with an angry smile. “Is it true that when you were in Petersburg you belonged to a secret society for practising beastly sensuality? Is it true that you could give lessons to the Marquis de Sade? Is it true that you decoyed and corrupted children? Speak, don't dare to lie,” he cried, beside himself. “Nikolay Stavrogin cannot lie to Shatov, who struck him in the face. Tell me everything, and if it's true I'll kill you, here, on the spot!” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Я эти слова говорил, но детей не я обижал, — произнес Ставрогин, но только после слишком долгого молчания. Он побледнел, и глаза его вспыхнули. |

|

“I did talk like that, but it was not I who outraged children,” Stavrogin brought out, after a silence that lasted too long. He turned pale and his eyes gleamed. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Но вы говорили! — властно продолжал Шатов, не сводя с него сверкающих глаз. — Правда ли, будто вы уверяли, что не знаете различия в красоте между какою-нибудь сладострастною, зверскою штукой и каким угодно подвигом, хотя бы даже жертвой жизнию для человечества? Правда ли, что вы в обоих полюсах нашли совпадение красоты, одинаковость наслаждения? |

|

“But you talked like that,” Shatov went on imperiously, keeping his flashing eyes fastened upon him. “Is it true that you declared that you saw no distinction in beauty between some brutal obscene action and any great exploit, even the sacrifice of life for the good of humanity? Is it true that you have found identical beauty, equal enjoyment, in both extremes?” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Так отвечать невозможно... я не хочу отвечать, — пробормотал Ставрогин, который очень бы мог встать и уйти, но не вставал и не уходил. |

|

“It's impossible to answer like this. . . . I won't answer,” muttered Stavrogin, who might well have got up and gone away, but who did not get up and go away. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Я тоже не знаю, почему зло скверно, а добро прекрасно, но я знаю, почему ощущение этого различия стирается и теряется у таких господ как Ставрогины, — не отставал весь дрожавший Шатов, — знаете ли, почему вы тогда женились, так позорно и подло? Именно потому, что тут позор и бессмыслица доходили до гениальности! О, вы не бродите с краю, а смело летите вниз головой. Вы женились по страсти к мучительству, по страсти к угрызениям совести, по сладострастию нравственному. Тут был нервный надрыв... Вызов здравому смыслу был уж слишком прельстителен! Ставрогин и плюгавая, скудоумная, нищая хромоножка! Когда вы прикусили ухо губернатору, чувствовали вы сладострастие? Чувствовали? Праздный, шатающийся барченок, чувствовали?

|

|

“I don't know either why evil is hateful and good is beautiful, but I know why the sense of that distinction is effaced and lost in people like the Stavrogins,” Shatov persisted, trembling all over. “Do you know why you made that base and shameful marriage? Simply because the shame and senselessness of it reached the pitch of genius! Oh, you are not one of those who linger on the brink. You fly head foremost. You married from a passion for martyrdom, from a craving for remorse, through moral sensuality. It was a laceration of the nerves . . . Defiance of common sense was too tempting. Stavrogin and a wretched, half-witted, crippled beggar! When you bit the governor's ear did you feel sensual pleasure? Did you? You idle, loafing, little snob. Did you 1” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Вы психолог, — бледнел всё больше и больше Ставрогин, — хотя в причинах моего брака вы отчасти ошиблись... Кто бы, впрочем, мог вам доставить все эти сведения, — усмехнулся он через силу, — неужто Кириллов? Но он не участвовал... |

|

“You're a psychologist,” said Stavrogin, turning paler and paler, “though you're partly mistaken as to the reasons of my marriage. But who can have given you all this information?” he asked, smiling, with an effort. “Was it Kirillov? But he had nothing to do with it.” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Вы бледнеете? |

|

“You turn pale.” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Чего, однако же, вы хотите? — возвысил наконец голос Николай Всеволодович, — я полчаса просидел под вашим кнутом и, по крайней мере, вы бы могли отпустить меня вежливо... если в самом деле не имеете никакой разумной цели поступать со мной таким образом. |

|

“But what is it you want?” Nikolay Vsyevolodovitch asked, raising his voice at last. “I've been sitting under your lash for the last half-hour, and you might at least let me go civilly. Unless you really have some reasonable object in treating me like this.” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Разумной цели? |

|

“Reasonable object?” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Без сомнения. В вашей обязанности, по крайней мере,. было объявить мне, наконец, вашу цель. Я всё ждал, что вы это сделаете, но нашел одну только исступленную злость. Прошу вас, отворите мне ворота. |

|

“Of course, you're in duty bound, anyway, to let me know your object. I've been expecting you to do so all the time, but you've shown me nothing so far but frenzied spite. I beg you to open the gate for me.” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Он встал со стула. Шатов неистово бросился вслед за ним. |

|

He got up from the chair. Shatov rushed frantically after him. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Целуйте землю, облейте слезами, просите прощения! — вскричал он, схватывая его за плечо. |

|

“Kiss the earth, water it with your tears, pray for forgiveness,” he cried, clutching him by the shoulder. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Я однако вас не убил... в то утро... а взял обе руки назад... — почти с болью проговорил Ставрогин, потупив глаза. |

|

“I didn't kill you . . . that morning, though . . . I drew back my hands . . .” Stavrogin brought out almost with anguish, keeping his eyes on the ground. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Договаривайте, договаривайте! вы пришли предупредить меня об опасности, вы допустили меня говорить, вы завтра хотите объявить о вашем браке публично!.. Разве я не вижу по лицу вашему, что вас борет какая-то грозная новая мысль... Ставрогин, для чего я осужден в вас верить вовеки веков? Разве мог бы я так говорить с другим? Я целомудрие имею, но я не побоялся моего нагиша, потому что со Ставрогиным говорил. Я не боялся окарикатурить великую мысль прикосновением моим, потому что Ставрогин слушал меня... Разве я не буду целовать следов ваших ног, когда вы уйдете? Я не могу вас вырвать из моего сердца, Николай Ставрогин! |

|

“Speak out! Speak out! You came to warn me of danger. You have let me speak. You mean to-morrow to announce your marriage publicly. . . . Do you suppose I don't see from your face that some new menacing idea is dominating you? . . . Stavrogin, why am I condemned to believe in you through all eternity? Could I speak like this to anyone else? I have modesty, but I am not ashamed of my nakedness because it's Stavrogin I am speaking to. I was not afraid of caricaturing a grand idea by handling it because Stavrogin was listening to me. . . . Shan't I kiss your footprints when you've gone? I can't tear you out of my heart, Nikolay Stavrogin!” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Мне жаль, что я не могу вас любить, Шатов, — холодно проговорил Николай Всеволодович. |

|

“I'm sorry I can't feel affection for you, Shatov,” Stavrogin replied coldly. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Знаю, что не можете, и знаю, что не лжете. Слушайте, я всё поправить могу: я достану вам зайца! |

|

“I know you can't, and I know you are not lying. Listen. I can set it all right. I can 'catch your hare' for you.” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Ставрогин молчал. |

|

Stavrogin did not speak. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Вы атеист, потому что вы барич, последний барич. Вы потеряли различие зла и добра, потому что перестали свой народ узнавать... Идет новое поколение, прямо из сердца народного, и не узнаете его вовсе, ни вы, ни Верховенские, сын и отец, ни я, потому что я тоже барич, я, сын вашего крепостного лакея Пашки... Слушайте, добудьте бога трудом; вся суть в этом, или исчезнете, как подлая плесень; трудом добудьте. |

|

“You're an atheist because you're a snob, a snob of the snobs. You've lost the distinction between good and evil because you've lost touch with your own people. A new generation is coming, straight from the heart of the people, and you will know nothing of it, neither you nor the Verhovenskys, father or son; nor I, for I'm a snob too — I, the son of your serf and lackey, Pashka. . . . Listen. Attain to God by work; it all lies in that; or disappear like rotten mildew. Attain to Him by work.” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Бога трудом? Каким трудом? |

|

“God by work? What sort of work?” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Мужицким. Идите, бросьте ваши богатства... А! вы смеетесь, вы боитесь, что выйдет кунштик? |

|

“Peasants' work. Go, give up all your wealth. . . . Ah! you laugh, you're afraid of some trick?” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Но Ставрогин не смеялся. |

|

But Stavrogin was not laughing. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Вы полагаете, что бога можно добыть трудом, и именно мужицким? — переговорил он, подумав, как будто, действительно, встретил что-то новое и серьезное, что стоило обдумать. — Кстати, — перешел он вдруг к новой мысли, — вы мне сейчас напомнили: знаете ли, что я вовсе не богат, так что нечего и бросать? Я почти не в состоянии обеспечить даже будущность Марьи Тимофеевны... Вот что еще: я пришел было вас просить, если можно вам, не оставить и впредь Марью Тимофеевну, так как вы одни могли бы иметь некоторое влияние на ее бедный ум... Я на всякий случай говорю. |

|

“You suppose that one may attain to God by work, and by peasants' work,” he repeated, reflecting as though he had really come across something new and serious which was worth considering. “By the way,” he passed suddenly to a new idea, “you reminded me just now. Do you know that I'm not rich at all, that I've nothing to give up? I'm scarcely in a position even to provide for Marya Timofyevna's future. . . . Another thing: I came to ask you if it would be possible for you to remain near Marya Timofyevna in the fixture, as you are the only person who has some influence over her poor brain. I say this so as to be prepared for anything.” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Хорошо, хорошо, вы про Марью Тимофеевну, — замахал рукой Шатов, держа в другой свечу, — хорошо, потом само собой... Слушайте, сходите к Тихону. |

|

“All right, all right. You're speaking of Marya Timofyevna,” said Shatov, waving one hand, while he held a candle in the other. “All right. Afterwards, of course. . . . Listen. Go to Tikhon.” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— К кому? |

|

“To whom?” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— К Тихону. Тихон, бывший архиерей, по болезни живет на покое, здесь в городе, в черте города, в нашем Ефимьевском Богородском монастыре. |

|

“To Tikhon, who used to be a bishop. He lives retired now, on account of illness, here in the town, in the Bogorodsky monastery.'' |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Это что же такое? |

|

“What do you mean?” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Ничего. К нему ездят и ходят. Сходите; чего вам? Ну чего вам? |

|

“Nothing. People go and see him. You go. What is it to you? What is it to you?” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— В первый раз слышу и... никогда еще не видывал этого сорта людей. Благодарю вас, схожу. |

|

“It's the first time I've heard of him, and . . . I've never seen anything of that sort of people. Thank you, I'll go.” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Сюда, |

|

“This way.” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— светил Шатов по лестнице, — ступайте, — распахнул он калитку на улицу. |

|

Shatov lighted him down the stairs. “Go along.” He flung open the gate into the street. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

— Я к вам больше не приду, Шатов, — тихо проговорил Ставрогин, шагая чрез калитку. |

|

“I shan't come to you any more, Shatov,” said Stavrogin quietly as he stepped through the gateway. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Темень и дождь продолжались попрежнему. |

|

The darkness and the rain continued as before. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

from Бесы – Demons or The Devils or The Possessed, 1871-1872,

by Фёдор Михайлович Достоевский – Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoyevsky

(* 30 October [N.S. 11 November] 1821 — 28 January [N.S. 9 February] 1881 †)

Часть вторая, Глава первая – Part II, Chapter 1 [emphasis added] |

|

| |

|

|

| |

Nearly the same composition is on the eastern and northern sides of Церковь Покрова на Нерли – the Church of the Intercession on the Nerl River. That pictured here is on the southern side, a stonecarve base relief of King Saint David the Psalmist flanked by birds and lions, symbolizing the conflict between good and evil. David holds a harp in his left hand, and with his right hand he crosses himself, stark symbolism reminding the world that King Saint David, like Abraham and Moses and other Old Testament prophets, is a Christian saint, not a Talmudic or atheist Jew. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

... Valaam Воскресенский Скит (Новоиерусалимский или Красный Скит) – Resurrection Skete, also known as the New Jerusalem or Red Skete . |

|

| |

|

|

| |

Perhaps the oldest extant wooden Church in Russia, Церковь Воскрешения Лазаря – Church of the Resurrection of Lazarus, built sometime betwen the XIV and XVI centuries, and according to one legend by the hand of Brother Lazarus – Лазарь Мурманский (1286-1391), founder of the Murom Holy Dormition Monastery – Муромский Свято-Успенский Монастырь, and revered as a saint. The Church was relocated from the site where it was built on the eastern shores of Lake Onega to Кижи–Kizhi Island in the middle of the lake. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Within the walls of the Holy Transfiguration Monastery in Murom – в Спасо-Преображенский монастырь в Муроме, viewed from exterior apses (East looking West), |

|

| |

Спасо-Преображенский Собор (XVI век) — Cathedral of the Transfiguration of the Savior (consecrated 1556), and

(to viewer's right) Церковь Покрова Богородицы — Church of the Intercession of the Virgin. |

|

| |

Closely associated with Saint David (Глеб – Гліб – Gleb), who was martyred in 1015 along with his brother, Saint Roman (Борис – Барыс – Boris),

by their half brother, Свѧтоплъкъ – Sviatopolk the Accursed – Святополк Окаянний – Святополк Окаянный, the monastery is one of the oldest in Russia.

First mentioned in 1096 in the «Повести временных лет» (the Tale of Bygone Years), the Transfiguration Monastery is held to date to the turn of the X to XI centuries. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

...Solovyetsky Monastery outer Wall with Успенская Башня – Assumption Tower and Святые Ворота – Holy Gate center . |

|

| Rise, and have no fear. |

|

This is my beloved Son, with whom I am well pleased; listen to him. |

the Holy Spirit |

Man proposes, God disposes |

|